The Sagherian Triangle: A Strategic Seating Arrangement

February 10, 2019

Early in my teaching career, I spent many solitary evenings designing seating arrangements. My impetus was to temper student behavioral concerns, and I found that strategically positioning children could drastically shift my classroom’s learning environment. Two of the most common considerations I made were separating friends who perpetually talked, and moving highly distractible students closer to me. Able to use my energy more efficiently, my lessons became more functional, my students happier. Still, over four years passed before I realized that a tactical seating chart also had the power to maximize math achievement.

During the summer of 2006, Dr. Yoram Sagher – professor of mathematics at Florida Atlantic University – trained me in elementary math teaching methods. He recommended a direct instruction approach with frequent informal assessments. Optimizing its power, he said, required strategic teacher and student positioning. Over the past 12 and-a-half years, I have worked hard to implement his pedagogical design. In the paragraphs below, I have tried to put his teachings and theories in writing, while threading in some of my own ideas

***

A great mathematical seating arrangement begins with the physical makeup of the classroom. The board should be positioned so that all students can clearly see teacher writing and/or projected images. This requires paired frontal seating. Each student has one discussion partner, and the teacher can comfortably stand next to each child.

The teacher arranges desks in a portrait, rather than landscape perspective, so that they can see most or all of their students at once (see Illustration 1). Simple eye contact bolsters student concentration. Without it, children feel disconnected from their learning and descend into distraction and disinterest.

Once the desks are configured, the teacher determines the position in which they’re most comfortable writing on the board. This decision dictates their line of vision and – in turn - where individual students will sit. They choose the spot where they will spend the most time instructing and, facing the empty classroom, spread their arms in a v-shape. The triangle that is created establishes the boundaries of their centralized vision.

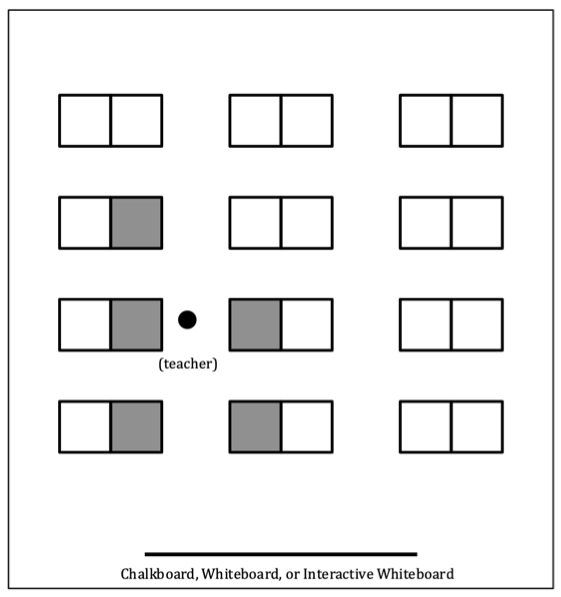

When creating a seating chart, the weakest and/or least attentive students are centered in the teacher’s vision, while the strongest and most focused sit in their periphery (see Illustration 2). This allows the teacher to maintain consistent eye contact with the most fragile students, and perform non-stigmatizing informal assessments.*

There is a misconception that physical proximity to a teacher incubates student focus. Struggling students are in a better position to learn anywhere inside the teacher’s triangle than they are outside of it - even if they are sitting in the back row.

After the instructor’s triangular vantage has been established, they assign strategic paired seating. Behavioral concerns are considered, but the instructor understands: Consistent, dynamic, well-planned lessons minimize disruptions. Each student is partnered with a classmate who will stretch their thinking during instruction and independent practice. This enriches every child’s mathematical experience, while allowing the teacher to concentrate their energy with students who need the most help.

While students practice independently, the instructor devotes most of their attention to the weakest 20% of the class. They position struggling students close to - but not necessarily beside - each other (see Illustration 3). By minimizing their own movement, they maximize their help time. They know that stronger students also have questions, but are more likely to solve their challenges when collaborating with a partner functioning on the same skill and/or conceptual level.

For more thoughts on classroom design and pedagogical theories, click on the button below.

Illustration 1.

Illustration 2.

Students sitting in the shaded seats are centered in the teacher’s triangular vision.

Illustration 3

The shaded seats are occupied by students who are likely to need the most teacher help.